Do Nothing

This year marks the 70th anniversary of what many scientists consider to be the most important invention of the 20th century: the transistor. The transistor is a sort of switch that either allows current to flow, or doesn’t. The idea of two conditions, or states, represented by “0” (no current/off) and “1” (current/on) is captured by the term “digital.” It is the transistor that transported us into the digital age.

Less than ten years after William Shockley and his fellow scientists at Bell Laboratories created the first prototype, the size of a transistor was scaled down to such an extent that half-a-dozen could be housed inside a radio one could hold in the palm of one’s hand. A decade later, transistor radios were ubiquitous. As a kid growing up in the San Fernando Valley, I could now take my favorite music along with me to the beach, and listen to Vin Scully and Chick Hearn through the filter of my pillow, long after “lights-out.”

Twenty years later, transistors, now in the thousands, enabled me to feed a stack of “IBM cards” – each one “key punched” – into a card reader that permitted the transistors to assume one digital state if a chad had been dislodged, and another if it hadn’t. Those transistors were packed into a massive computer that literally filled a large (off limits) room in UCLA’s engineering building, Boelter Hall.

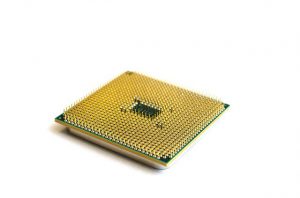

With miniaturization, the digital revolution commenced in earnest. The development of the integrated circuit and the microprocessor enabled tens of millions of transistors to be “printed” onto a surface the size of a postage stamp. Today, the computing power of my smart phone dwarfs that of the gigantic computer that crunched my dissertation data at UCLA. Now, it’s not just my music that I can take along with me to the beach – it’s the entire world.

With miniaturization, the digital revolution commenced in earnest. The development of the integrated circuit and the microprocessor enabled tens of millions of transistors to be “printed” onto a surface the size of a postage stamp. Today, the computing power of my smart phone dwarfs that of the gigantic computer that crunched my dissertation data at UCLA. Now, it’s not just my music that I can take along with me to the beach – it’s the entire world.

It is difficult to overestimate the impact of our ability to cram increasingly larger numbers of transistors into ever-smaller spaces. In 1968-69, I spent my junior year abroad in Jerusalem, Israel. Back then, it took an average of eight days for a letter to make its way from there to Los Angeles. If our parents worried about us, they could always write, but they’d do so knowing that they’d be lucky to receive a response within three weeks’ time. To phone home, one had to reserve a date and time at the central post office, from where the call had to be placed by a special operator. (It cost a fortune, so nobody did it.)

If one got lost, one could not rely upon GPS and Google Maps to find one’s way. One had to ask for help, and do so without benefit of Google Translate, or any of today’s ever-more proficient apps that are removing any lingering shreds of motivation to actually learn a foreign language. If one wished to ask someone out on a date, there was almost no getting around the necessity of doing so face-to-face. Telephone service wasn’t universally available, particularly dependable, or cheap. Thus, there was no escape from the risk of rejection in real time, up-close and personal.. If one wished to pursue knowledge, one was pretty much forced to read books. Which required accessing them. Physically. Tough as it was, such challenges were instrumental in making my junior year the bridge to my independence. I often think how different the experience would have been had I been carrying my mother around in my pocket. (I know that sounds weird, but you know exactly what I mean.)

Today, before we embark upon a vacation, we’ve already been virtually everywhere we’re about to go, and done everything we’re about to do. We’ve taken 3-D tours of the hotel rooms in which we’re going to reside, perused the menus of restaurants in which we’re going to eat and read scores of reviews of the experience we’ve decided to have, pre-programed the routes we plan to take on public transportation apps, and watched other people’s experiences at the venues we intend to visit.

Once we’re “there,” we’ll do our best to make ourselves feel as if we’ve never left. With our security camera systems, Alexa devices, and Nest home environment devices in place, we’ll be keeping an eye on things at home, and using our Ring Doorbell systems to see who’s knocking at the door. We’ll take our friends and family along with us via our preferred array of social media platforms, and will make sure the world knows about the intimate dining experience we’re enjoying at that out-of-the-way little bistro, as it’s happening. We will then check our phones, or other handheld devices, every few minutes to see how many of our friends have “liked” and/or commented upon our posts.

Transistors continue to shrink, and raw computing power continues to expand. In 1965, Intel co-founder Gordon Moore predicted that the number of transistors in an integrated circuit would double every year, a time-frame he later revised to every two years. More than fifty years later, “Moore’s Law” remains largely intact.

Are we ready to stop and take a breath? Hardly. Relaxation is a vanishing art. Increasingly, we cannot escape our portable devices. The smaller the transistor, the greater the rate at which we monitor our obligations, relationships, finances, news, weather, sports, gossip, continues to accelerate. And with every mouse click and finger tap, we’re not just consuming data; we’re producing information that is captured and analyzed by algorithmic programs designed to lure us ever deeper in. And sell us stuff. Lots and lots of stuff…

We now sport digital “wearables” designed to monitor our health. With increasing miniaturization today’s apparel will look crudely outdated in just a few years. It won’t be long before implanted devices will let us know the extent to which we’re actually alive.

The implications for educators are so staggering that few of us have the resolve, or the wherewithal to begin addressing them. How, for example, are we supposed to know how to prepare students for jobs that don’t yet exist? Answering that question will probably require a paradigm shift in the way we, ourselves, think. But by the time we accomplish such a task, if ever we should, chances are that our new way of thinking will be obsolete.

You’ve read more than enough by now. As you prepare to take time off sometime during the course of the coming months, here’s my wish for you: Pretend that it’s 1950…just for a day. OK…just for a few hours. Pick up a trashy novel, pour yourself a cold one, and tune out. Don a pair of earphones and listen to your favorite album from start to finish with your eyes closed. Drive to the wide-open-spaces, camp out and watch the stars. And if you can’t do any of that, take 10 minutes and do nothing. Yes, nothing. Just be. And then help me do it. You can find me on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.